Navigating the New Normal in Global Trade: Building Resilient Manufacturing Strategies

As trade agreements shift, tariffs fluctuate, and geopolitical tensions escalate, manufacturers need to be more strategic and adaptable than ever before. Old assumptions about cost, scale, and stability no longer hold in today’s increasingly fragmented global trade environment, and there is mounting pressure for manufacturers to rethink how and where they produce goods.

However, there are practical strategies manufacturers can use to improve the flexibility and resilience of their operations by designing supply chains and production networks that can adapt quickly to sudden changes. The organizations that come out on top in this environment will be those that can identify vulnerabilities in current configurations and rapidly adjust operations to reduce risk and manage costs.

Whether you’re preparing for the next disruption or aiming to manage long-term operational risks, it’s important to understand the factors impacting the current global trade landscape, what’s likely to come next, and what actions you can take to stay competitive in unpredictable conditions.

How did we get here? The emergence and future of a volatile global trade environment

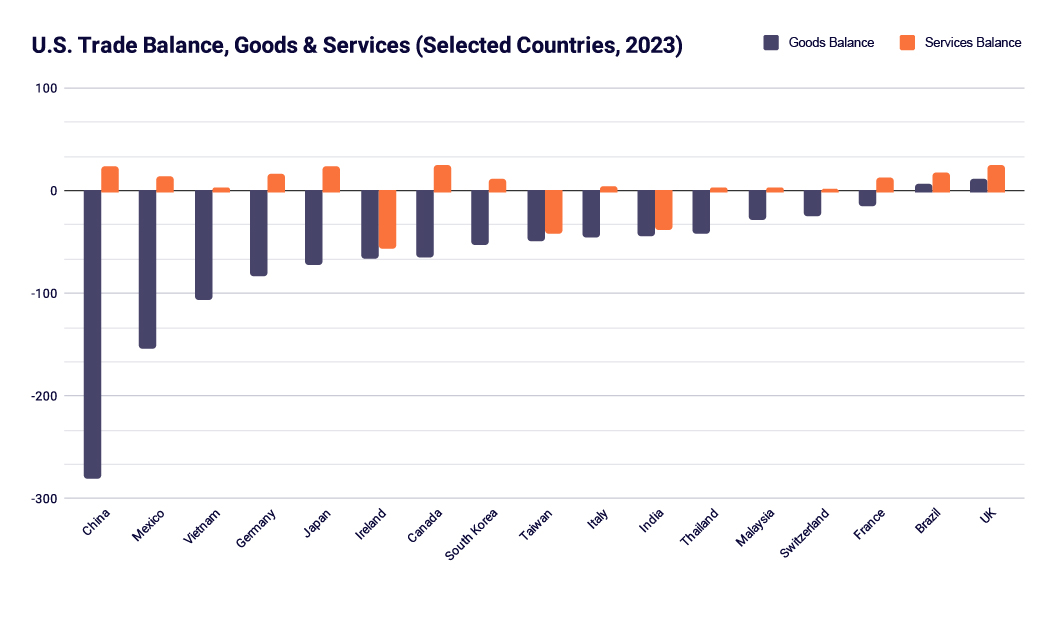

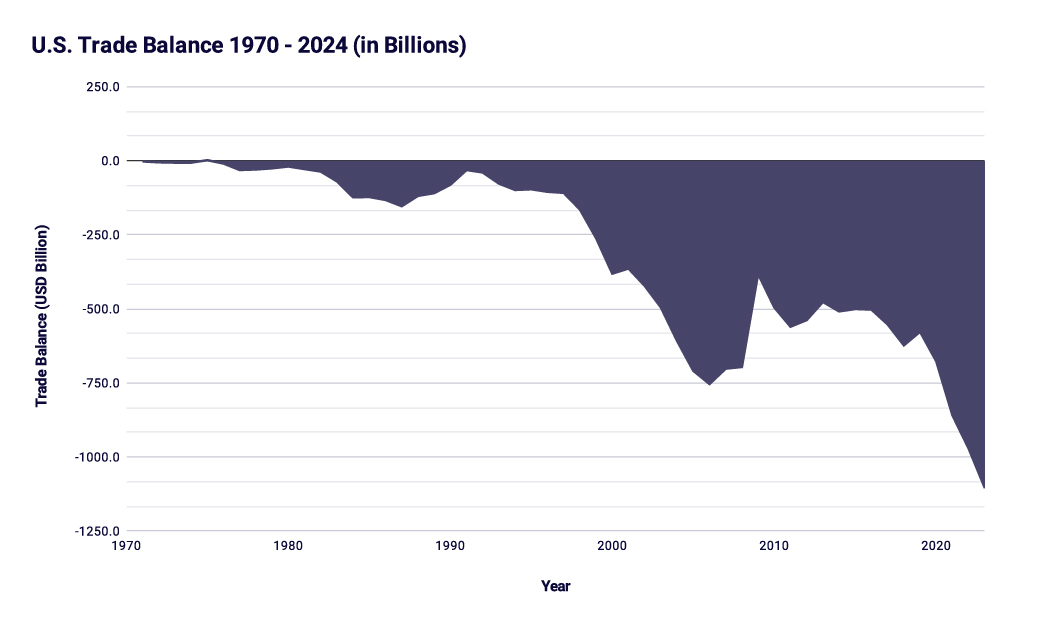

After World War II, a multilateral trading system evolved, culminating in the World Trade Organization (WTO) and supplementary regional trading blocs. In this trading regime, stability was the norm, with consistent, negotiated arrangements punctuated by occasional renegotiations. Over this period, the system became not only more stable but generally more open, with lower and fewer tariffs, albeit with increasingly elaborate non-tariff barriers (NTBs). This system relied on the United States to remain largely open to imports, absorbing manufactured exports from most other Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries, while exporting services.

Source: United States Census Bureau

Recently, the new U.S. administration made significant changes to this trading regime. This was only the final step for a trade ecosystem that had been eroding over time. There have been many signs of this breakdown:

- Resilience, self-reliance, and national security have been overtaking efficiency, scale, and low-cost production as national goals. After COVID-19 exposed vulnerabilities, China, the EU, and the U.S. are all aiming to near-shore, reshore, and “localize” key production.

- Trade and technology have been weaponized (e.g., export bans), and industrial policy, with its attendant protectionism, has spread — even to the U.S.

- Regional blocs have emerged, including the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA); the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and the Digital Silk Road (DSR); India, ASEAN and the EU; and South-South trade.

- The erosion of WTO authority and associated multilateral norms.

There are reasons to believe this is a permanent rupture and not a shock that can be recovered from. The forceful end of the WTO, USMCA, and other multilateral (and bilateral) trade agreements by the U.S. (followed by most other major traders) will make it very difficult to put the previous state back together again. Even if new multilateral agreements could be made, why would any partners believe the U.S. would honor them? Trust must first be rebuilt.

In addition, important conditions attending the development and maintenance of the WTO regime no longer hold: American economic dominance; American leadership and support for multilateral institutions supporting open trade (the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) and then the WTO, the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the World Bank); and Cold War geopolitics that encouraged the U.S. to support open trade with allies. Without these conditions, it seems unlikely that the global trade environment would return to its prior state.

We can’t know the details of whatever new trading regime evolves, but a few characteristics seem likely:

- More trade through bilateral agreements and less through multilateral agreements (e.g., WTO rules only), as bilateral agreements are easier to reach and to modify than multilateral agreements among several or many countries.

- Multilateral agreements that persist will be more regional and include fewer countries.

- NTBs will be complementary to tariffs — lower stated tariffs will be offset by more NTBs (and vice versa).

The result is likely to be a patchwork of shifting trade agreements — with tariffs; NTBs (such as rules of origin, labor and environmental standards, quotas, subsidies, and certification requirements); and exchange rate regimes and currency policies all changing more and more frequently than was the case in the trading regime just ending.

The effects will be felt in the prices and availability of both manufacturing inputs and finished goods at their destinations.

Configuring production and supply chains for resilience

Given these uncertainties, there is a lot of concern about supply chain resilience. Often, supply chain resilience is described as the ability to withstand disruptions and can be measured across three dimensions:

- Time to Recover (TTR)

- On Time In Full delivery rate (OTIF)

- Order cycle time

But what does resilience mean in the context of shifting trade rules? There is generally some persistence to changes in tariffs, NTBs, or currency regimes — at least long enough to make some adjustments in sourcing or what gets produced at each location. While this has not been true for recent disruptions, that is an exception and not the norm. Typically, changes stick around long enough to offer leaders opportunities to shift strategies and compensate.

A more comprehensive, strategic perspective is needed to navigate this new environment:

- Viewing your set of production facilities and suppliers as a configuration, resilience means how well that configuration can adapt to step changes in tariffs, NTBs, or currency regimes. One way to measure that is in total production cost (the cost to manufacture the full set of products to meet demand for a quarter or a year). How much does total production cost change when particular tariffs change, or exchange rates shift, or export controls spike the price of a key input for months or years?

- Building a profile of how the total production cost changes in response to plausible scenarios can tell you how vulnerable you are to such shifts. And if you are configured such that you can shift (some) supply inputs to countries unaffected by changing trade rules, or move production of (some) finished goods to factories similarly un- (or less) affected, you can reduce the impact of the trade rules change on total production cost.

What does this look like in action?

Recently, my team helped a Fortune 50 manufacturer of large, durable goods with a sprawling global production base optimize “what gets made where” to reduce costs, improve flexibility, and increase their resilience to shocks in trading conditions. We worked closely with executives and an operational core team to:

- Establish, define, and measure the key parameters to balance, including cost, quality, risk, and flexibility

- Determine and acquire key inputs such as product data, labor costs, tariffs, exchange rates, shipping rates, production costs, component/raw material supply costs, and more

- Develop target scenarios and iteratively model both the financial and non-financial impacts of each scenario using a comprehensive multi-variant optimization model

- Assess results and recommend an optimal global manufacturing network, including dramatic changes in both product modularity and manufacturing footprint

- Establish a prioritized action plan for recommendations

The company’s new manufacturing strategy is currently in the implementation stage. Impacts include:

- Projected savings in operating costs that exceed $100 million annually

- Increased network flexibility and reduced risk

- Strategic uplift for other business lines across the company that are now integrating our approach

The most resilient production configurations will have some overlapping manufacturing capabilities and be dispersed enough to reduce the impact of repeated, unpredictable trade rules shifts.

Supply chain and production resilience is not costless — you must build some redundant manufacturing capacity, maintain a distributed portfolio of key suppliers, and have the ability in your management systems to adjust sourcing and S&OP to adapt to changes in trading conditions.

The only way to know if this cost is worthwhile is to model your current configuration of suppliers, factories, and sales destinations and test it against changes in tariffs, NTBs, and exchange rates. Within your current capabilities, can you make changes (in sourcing or in what is produced at each factory) to reduce the impact of trade shocks? Are there changes that can be made to your configuration (e.g., add a production line at a particular factory or add a supplier from a different region) that would materially improve your resilience? Modeling and optimization can point you to the answers.

Adapting to the new normal

In the volatile trading conditions that are emerging, manufacturers that can build balanced, flexible supply and production bases will be best suited to navigate shifting market conditions.

This requires access to specialized expertise that can guide real-time decision-making. That’s where Catalant comes in. This community of seasoned Experts — many with deep experience in global trade, manufacturing operations, and supply chain strategy — can help you assess vulnerabilities, identify opportunities, and design resilient, adaptive solutions.

As trade volatility accelerates, partnering with Catalant ensures you’re not navigating it alone — you’re backed by Experts who can help you stay ahead of the competition and thrive in unpredictable markets.

Is your supply chain resilient? Catalant can help.

Let’s TalkMeet the Author

A principal at eos consulting, Byron Winn has worked with global OEMs such as John Deere and Cummins (as well as industrial suppliers deep in the value chain) to build and execute growth strategies (where to compete, how to win), manufacturing strategies (what to build where, and how), and Go To Market programs (including market mapping and segmentation; value propositions; channel and marketing strategies). He is a former fighter pilot and a Harvard Ph.D.

Related Articles

Share Article