A Leader’s Guide to Effective Strategy Execution

Organizational complexity is a major challenge when it comes to effective strategy execution. Most enterprises have matured by driving functional excellence in areas like manufacturing, supply chain, and sales, but when it’s time to drive large cross-functional initiatives aimed at improving customer value, the vertical structure becomes an impediment to success.

Most organizations will reach a point where they recognize that their inability to deliver cross-functionally is a big problem. Competition from both traditional foes and disruptors will eventually overwhelm the enterprise if not addressed.

As I like to say, your customers don’t want to pay for your inefficiencies.

So how can leaders drive complex work across multiple functional domains? In my career (I was most recently an EVP at Bose), I’ve relied on a straightforward process I call “Framing it up” to guide large initiatives and get work moving effectively across the organization.

Effective Strategy Execution: 5 Steps to Framing It Up

Framing it up is a process designed to neutralize the natural resistance created by vertical functions. The process requires commitment at multiple levels of the organization, but when applied correctly, the process mitigates politics, misalignment of goals, and other common roadblocks related to strategy execution — it also infuses agility into your strategy execution.

1. Define the results.

Specific, measurable outcomes are critical to any strategic initiative, and yet frequently leaders find themselves at odds with other functional areas over what their objectives are. Goals that sounded clear in the boardroom might now be interpreted very differently by those tasked with meeting them.

The way to avoid this is through a leadership meeting focused solely and specifically on defining the results that are needed for the success of the enterprise initiative. This meeting can last anywhere from one to four hours, and the only topic of discussion is bringing clarity and alignment on the results. No skipping ahead to functional or project plans, no discussion of staffing or resources.

Most importantly, no one leaves until the team is aligned on results.

2. Define the work.

Once the leadership team has aligned on the results, a somewhat broader team gets together to define the work necessary to reach those results. This broader group includes functional heads and other stakeholders who may not have been part of the results meeting.

As with the prior step, this one is focused only on defining the work. Re-litigating results that were defined and aligned is out of bounds, as is skipping ahead to discussing staffing or resources. The output of step 2, which might take a few weeks of development, should be agnostic about cost or management hierarchy.

During this process, you can expect to surface some “collisions,” which is a term I use to describe the friction that arises when a person or group fails to understand why they are being asked to complete the work as defined. If they don’t understand the intricacies and interdependencies of their work, they’re bound to let others down. These meetings should help draw these collisions out before they cause damage.

3. Define the skills.

Once the organization is aligned on the results and the work required, it’s time to define the skills and resources needed to get there.

It’s critical at this stage to limit discussion to the skills and capabilities necessary to complete the work — not the people. Once you start discussing specific names or functional groups, you invite forms of functional resistance into the conversation and people start getting protective of their teams. Step 4 is designed to apportion the work appropriately.

4. Close skill gaps.

Only after securing complete buy-in on the skills and capabilities should the cross-functional team start cataloging the people available for the work. In many (possibly most) cases, you’ll notice some gaps between the skills needed and the skills available. At this stage, your human resources team should be involved to help proactively identify and plan to mitigate any of these gaps.

This step also requires a regular report on how the organization is progressing toward closing those skills gaps. Whether through full-time hires or consultants working on short-term projects, the goal is to uplevel the organization to drive a specific set of objectives.

5. Lead the team.

Complex cross-functional initiatives require strong leadership. In my experience, these initiatives are the best training grounds for future leaders. The organization should seek out promising talent and put them at the helm of work like this as the project leader. The project leader should also have a certified change management leader assigned to her/him because we need to not only account for the technical execution across the enterprise but the people side of change as well. Both of these roles report to and are accountable to the Executive Sponsor.

I’ve found that effective leadership involves weekly status meetings — typically 90 minutes — in which the Executive Sponsor’s only action item is removing obstacles that the team faces in execution. As the team demonstrates progress, has managed through all of the vertical “collisions,” and begins to operate effectively through the tiers within the organization it may be evident that weekly status meetings are no longer required.

Effective Strategy Execution

A visual management tool can be very powerful for leaders managing large complex work streams across multiple functions and geographies. At this point, the Executive Sponsor will periodically “go to the gemba” (where the work is happening) to witness the progress being made toward the results that were committed to.

When it all comes together, high-performing organizations can break down the traditional barriers that prevent them from executing their strategies. In my time at Bose, I saw what can happen when people are committed to success with their hearts, minds, and souls. Even better, the tactics and processes we used to get there — in the face of enormous complexity — are already available to any organization.

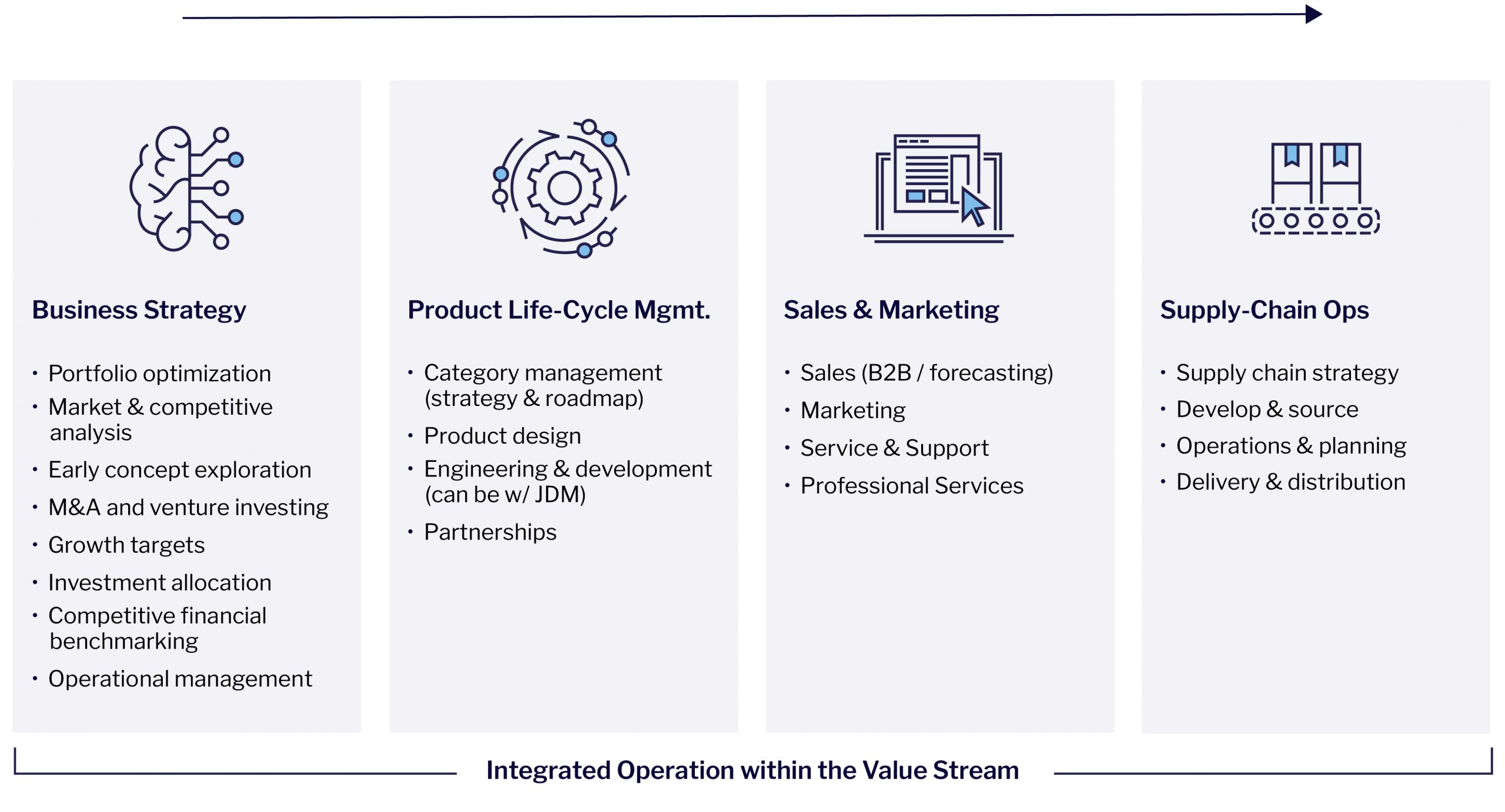

The Extended Value Stream:

Identify independent consultants who can support effective strategy execution.

Get in TouchRelated Articles

Share Article