3 Strategic Lessons from Intel’s Struggles

Since the year 2000, 52% of the S&P 500 has disappeared; gobbled up by competitors, withered into obscurity, or cast outright into the history books. And while consultants and authors have produced a seemingly limitless library of frameworks, strategies, and best practices for avoiding disruption, the carnage continues. Because while the diagnosis is simple — big companies fail because they’re slow — the treatment plan is much more difficult to define.

Consider Intel, one of the foundational companies in Silicon Valley. Founded in 1968, Intel evolved from a memory chip maker to the world’s leading microprocessor manufacturer by 1992. The company’s winning strategy was firmly rooted in integration — by consolidating the design and manufacturing of its microprocessors, Intel had a lasting competitive advantage that solidified its position at the top of the microprocessor market.

However, what was once its strength became its weakness, as Intel struggled to adapt quickly to the rise of smartphones, machine learning, cryptocurrency, and other trends that required new kinds of chips. Companies like AMD, TSMC, GlobalFoundries were faster in those markets precisely because they separated design from manufacturing. As the global market for x86-powered personal computers waned, Intel struggled. CEO Bob Swan told investors the company expected a decline in revenues for 2019.

In one month, Intel had lost 23% of its value.

Of course, this is a relatively simplistic narrative of disruption. As former Microsoft executive Steven Sinofsky said about Intel’s woes in 2018, disruption is rarely so tidy.

Too often people look to a single factor that causes disruption — sort of like how zippers disrupted buttons or something. In reality, disruption of a company is often a host of inter-connected issues with no single issue dominating. Together these might be a theme — mobile computing — but within that it is many things working in concert to cause problems.”

Steven Sinofsky, Learning While Shipping

The problem is real and isn’t one thing. It’s market pressure. It’s changing workforce expectations. It’s new technologies. It’s rising costs. It’s new competitors. It’s regulations. It’s all of the above.

3 Strategic Lessons from Intel’s Struggles

Here are three lessons from Intel’s struggles

1. Intel weathered plenty of storms before.

In 1986, inaccurate forecasts for microprocessors caught up with Intel, creating downward pressure on prices. The result was the company’s first-ever year-over-year losses and layoffs of over 7,000 people. Intel responded by doubling down on its integration strategy, mostly leaving the memory market and investing over $200 million to modernize its manufacturing processes. By 1992, Intel was one of the most valuable companies in the world.

In the face of a conventional threat, Intel’s strategy worked. However, today’s threats are far less conventional. Large enterprises can’t count on big bet investments or singular product visions — and they can’t counterattack on all fronts unless they build up institutional speed.

2. Because the company saw disruption coming and still couldn’t stop it.

The struggle at Intel is due to a lot of things, but lack of brain power isn’t one of them. The board and leadership team at Intel is packed with successful executives from a variety of backgrounds. Current CEO Bob Swan has leadership experience in startups and large organizations, and the executive management team is full of accomplished, talented people. They are well aware of the threats the organization faces.

In fact, Intel began to diversify its product lines and strategies years ago, dipping into the Internet of Things (IoT), non-volatile memory, autonomous vehicles, and more. But while some of those areas show signs of promise, according to analysts, the organization is having difficulty bringing new technologies to market in a timely-enough way to kick-start growth. Even worse, the organization missed a big milestone in its 10nm chip production just as competitor AMD released its third-generation Ryzen chips to great reviews.

3. The changes happened quickly.

As recently as January 2018, Intel was surging. Its 2017 revenues reached record numbers, partly on the strength of unexpected demand for PCs. The results thrilled Wall Street, which celebrated the organization for overcoming problems resulting from two different security vulnerabilities disclosed shortly before its earnings report.

Six months later, CEO Bob Krzanich was out. One year later, CEO Bob Swan faces scrutiny over the company’s decreasing earnings. Some analysts openly question whether the organization’s leadership is capable of righting the ship. Gone are the days of the long, slow decline. Today’s enterprises face threats that are both existential and immediate.

Big Boats and Flotillas

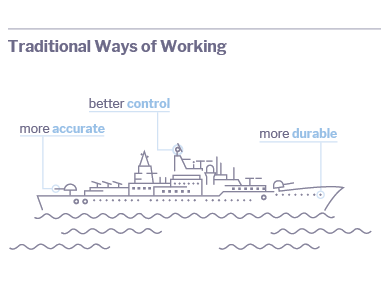

Last year, a high-level executive from a Fortune 50 oil & gas company told Catalant CEO Pat Petitti that running a large organization was like piloting a large cargo ship. The captain of the ship might spot a dangerous obstacle on the horizon and order the ship’s crew to avoid it. But the only way to turn the ship is for each crew member to shout instructions to those working below them until the final order “turn to port” reaches those working in the engine room — hopefully, before a new threat emerges in that direction also.

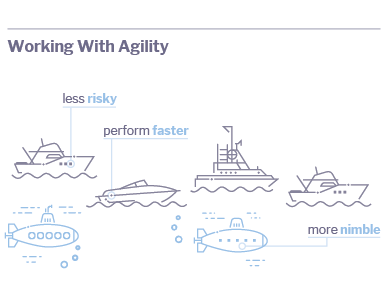

The advantages of a big boat are real. If the seas are calm and the threats are easily spotted from far away, the big boat is unstoppable. Flotillas, on the other hand, are optimized for speed. Flotillas can nimbly change course, approach multiple destinations at once, and add or reduce resources easily. They can also operate more like a network than a hierarchy if needed.

We call this approach business agility.

Business agility is the ability of an organization to move faster without losing stability. To become more agile, smart organizations like Anheuser-Busch InBev, Unilever, and General Electric are moving toward more agile ways of getting their most important work done. Not only do these organizations realize value more quickly, but they effectively de-risk their important projects by adopting a flexible, iterative approach.

Empowered by forward-thinking executives and enabled by the Catalant platform, these organizations are finding new ways to prioritize strategic initiatives, break down the work required to execute those initiatives, access and deploy the right people and capabilities to the right work, and gain full visibility into all mission-critical work in one place.